an inside out mine tunnel.

Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, Salt Lake City, Utah. (Adjunct Exhibition, April 24 - 1 August 2015).

(photograph by Jared Stephensen)

(photograph by Jared Stephensen)

After graduate school, my first art-related job was working for an arts organization in a neighborhood that evolved around the Spiro Mine Tunnel in Park City, Utah. I lived above the mine shaft and as I walked by its dark, barred entrance daily on the way to and from work, I began to imagine what an inside-out mine tunnel might be - one where what we value is not what is excavated from the land, but rather what we do on our local landscape. As our actions and repercussions of our activities become our focus, how can we conceive of them as a precious metal whose dynamic can be recognized and honored?

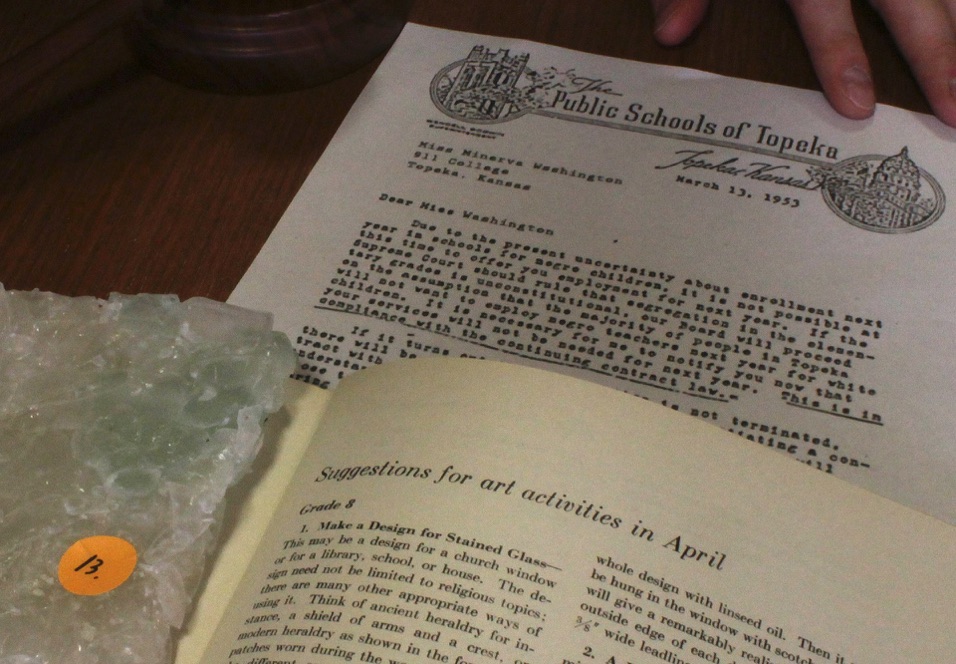

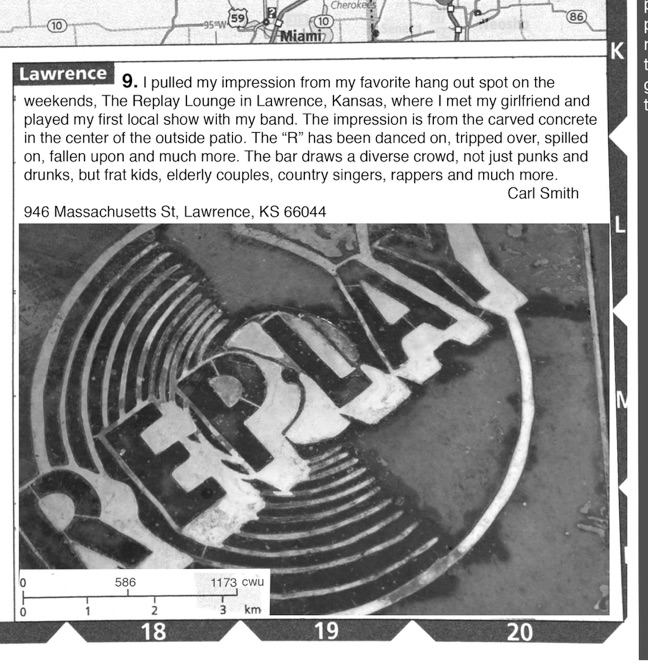

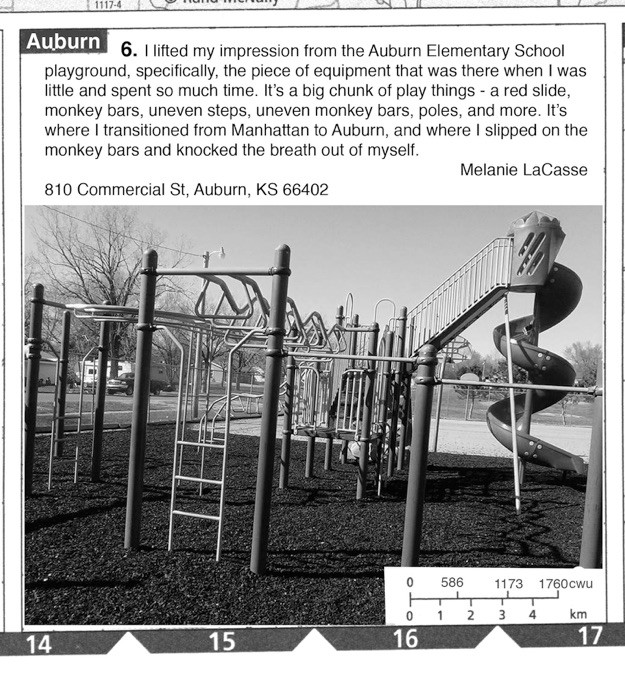

Six years after having been inspired by my time in Utah, I collaborated with my Three-Dimensional Design students at Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. Our goal was to distill significant personal or social experiences into tangible, reflective objects. I provided my students, myself included, with a chunk of soft wax to lift impressions of our sites in our communities that we cherish as a way to capture and reflect on the experiences in our region. In addition to lifting impressions, we had to find glass from our site, perhaps a bottle or a broken window pane. We then made investment molds of our impressions, and cast those molds by re-melting our found glass into them to create gems of those facets of our community.

Map and Key:

As a companion to the table of artifacts, we created a 3ft x 4ft map pinpointing where the impressions were taken of the experiences-turned-artifact. To tie the map back to the project’s roots in Park City, we applied a unique key developed by a technique miner’s used to measure distance in the Spiro Mine Tunnel. Researchers from the University of Utah, perplexed at how the miners were able to bore the Spiro Mine Tunnel in Park City perfectly straight, even more so than the University’s lasers could align, explained that the miners had devised a system using candles and washers, which my students and I were able to mimic in class. The miners, deep in the pitch-black tunnel, determined where to bore into the rock by first lighting a candle suspended from the ceiling. Then they would suspend a washer in the air by a string from the ceiling at the same level as the candle to cast a large shadow of a circle on the terminal wall of the tunnel. Then the miners suspended a second washer from the ceiling and centered the smaller shadow of the second washer within the illuminated center hole of the first washer’s larger shadow. Thus, by lining up the candlelight, the two washers, and centering their shadows on the wall, they were able to bore a straight line.

My students and I were able to accurately recreate this technique in a darkened room with our candle held at a maximum of nine feet away from the wall. That distance - nine feet - became our standard unit of measurement, which we call candle-washer units, for our map of Kansas.

Here are some examples from Washburn University design student participants:

Copyright © 2010 - 2017 Marin Abell. info@marinabell.org

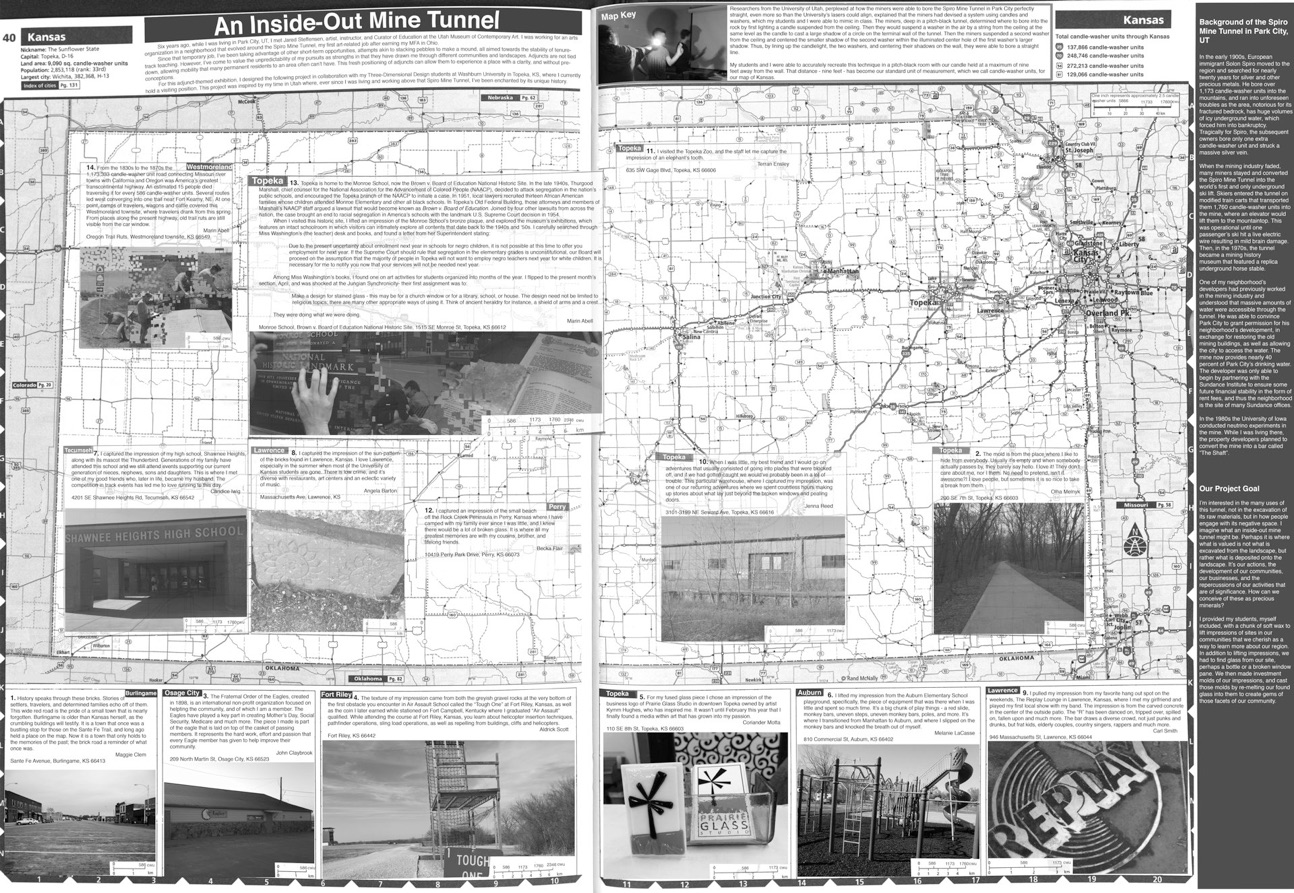

One of my molds, for example, involved Topeka’s role in moving toward racial integration of public schools. Topeka is home to the Monroe School, now the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site. In the late 1940s, Thurgood Marshall, chief counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), attacked public school segregation, and encouraged the Topeka branch of the NAACP to initiate a case. In 1951, local lawyers recruited 13 African American families whose children attended Monroe Elementary and other all black schools to participate in a lawsuit that became known as Brown v. Board of Education. Joined by four other lawsuits from across the nation, the case legally ended racial segregation in America’s schools with the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1954.

When I visited this historic site, I lifted an impression of the Monroe School’s bronze plaque, and explored the museum’s exhibitions, which features an intact schoolroom in which visitors can explore all the contents that date back to the 1940s and ‘50s. I carefully searched through Ms. Washington’s (the teacher) desk and books, and found a letter from her superintendent stating:

Due to the present uncertainty about

enrollment next year in schools for negro

children, it is not possible at this time to

offer you employment for next year. If the

Supreme Court should rule that segregation

in the elementary grades is

unconstitutional, our Board will proceed on

the assumption that the majority of people

in Topeka will not want to employ negro

teachers next year for white children. It is

necessary for me to notify you now that

your services will not be needed next year.

Among Ms. Washington’s books, I found one on student art activities organized into months of the year. I flipped to the present month’s section, April, and was stunned at the Jungian synchronicity - their first assignment was to:

Make a design for stained glass - this

may be for a church window or for a library,

school, or house. The design need not be

limited to religious topics; there are many

other appropriate ways of using it. Think of

ancient heraldry for instance, a shield of

arms and a crest...

They were doing what we were doing, and in the same month we were doing it!

Our collective objects were exhibited at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in Salt Lake City, displaying our experiences transformed into material, reflecting artifacts that had spilled out of a sand-filled bucket into a miner’s sifter and onto a make-shift table for viewers to examine.

marin abell